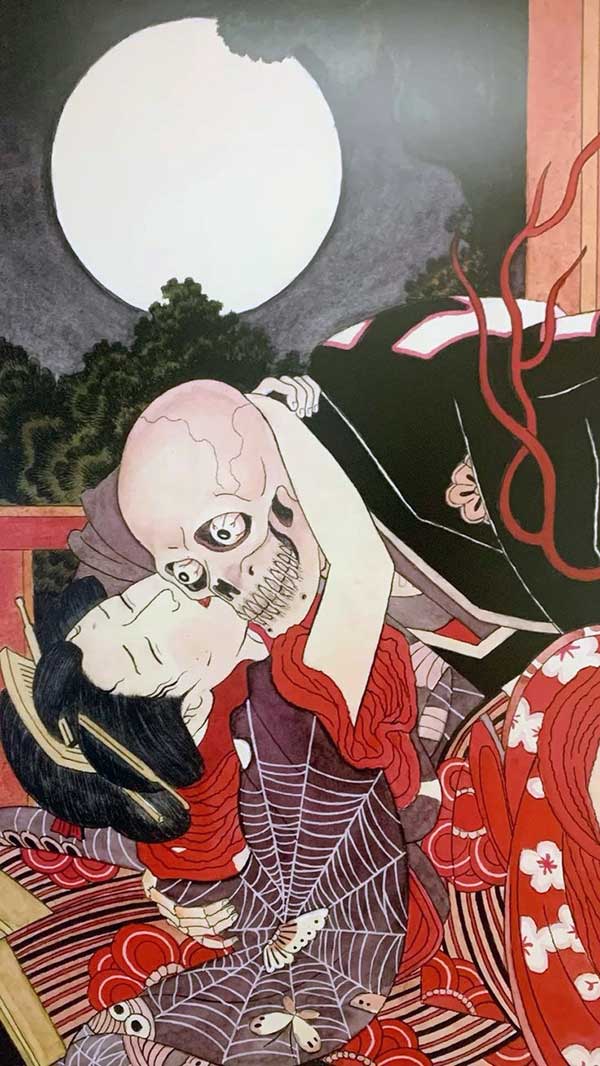

The Ukiyo-e Masters of Fear: Edo Period Horror

1. Iconic Japanese Horror Art: Yoshitoshi’s Masterpieces

Tsukioka Yoshitoshi didn’t just paint ghosts – he imprisoned their agony. Take The Ghost of Oiwa (1885). Her single eye swivels toward you like a dying moon. Hair splinters like cracked ice. A muddle of different artistic styles can create captivating pieces in Asian art, and you can see how he mixes beauty with decay. Oiwa was poisoned by her husband – a kabuki actor – so she haunts every performance of her story. True terror: Actors still visit her Tokyo shrine to beg forgiveness before shows. This isn’t just artwork – it’s psychological horror carved in ink. Yoshitoshi wrenched emotion from every brushstroke, turning betrayal into iconic imagery that still reflects the supernatural themes found in Japanese horror art and makes for an eerie viewing experience today.

2. Tsukioka Yoshitoshi’s Supernatural Obsessions

Here’s the twist: Yoshitoshi wrestled with madness himself. His One Hundred Ghost Stories series jettisoned polite Edo traditions. One print shows a lantern sprouting skeletal hands to strangle a samurai. Another depicts a woman birthing bloodied skeletons onto tatami mats. Yeah, it’s personal. After the Meiji Restoration, he watched westernization bulldoze old Japan. These prints? They’re his raw scream against cultural loss. He draped vengeful ghosts in Victorian gowns – grotesque fusions of East and West. Critics called them “disturbed.” He called them exorcisms.

3. Yūrei: Anatomy of a Japanese Ghost

Yūrei aren’t just “spirits.” Their white kimono? Burial shrouds for the dishonored dead. Floating in the realm of the supernatural, much like the yurei of Japanese folklore? No feet – forever trapped between worlds. That hair? Not just style – it symbolizes rage festering like mold in a damp grave. Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Oiwa (1836) leers with her iconic drooping eye and mouth twisted in eternal pain. Why the disfigurement? Edo folks believed violent death deformed the soul – and that deformity became power. No wonder Sadako in The Ring crawled from wells with hair masking her face. Modern manga artists still copy this symbolism: hair always swirls like smoke around vengeful ghosts.

The Haunting World of Japanese Folklore

4. Yokai: Japan’s Supernatural Monster Mythology

Yokai skitter through Japanese folklore like cockroaches in a Kyoto inn. Kappa drag kids into rivers to steal their souls. Kuchisake-onna saws mouths ear-to-ear with rusty scissors. Kuniyoshi crammed his art with them – like Takiyasha the Witch Summons a Skeleton Specter (1844). See that colossal bone monster towering over shattered palace screens? It’s not fantasy – it’s folk art as cultural memory. Edo period peasants genuinely saw yokai in creaking floors and midnight winds. Farmers left cucumbers for kappa to protect crops. Horror manga like GeGeGe no Kitaro keeps these supernatural beings alive today – proof that monsters outlive empires, just as the tales of yokai and mononoke have endured through the ages.

5. Utagawa Kuniyoshi’s Grotesque Beauty

Utagawa Kuniyoshi hacked ukiyo-e rules like a samurai beheading demons. Samurai battling giant, grinning cats? Check. Demons vomiting frogs onto screaming villagers? Done. His Earth Spider Generates Demons (1843) swirls with gore – spider silk morphing into supernatural snakes while warriors stab blindly. But here’s the genius: that spider’s face is a human bureaucrat’s sneer. He masked critiques of corrupt Tokugawa officials as monster tales. Censors banned him twice for “disturbing content.” Guess what? He drew angrier. His work pioneered the grotesque style that fuels manga gore today.

Eerie Tales: The Ghost Stories that Inspire Modern Manga

6. Japanese Ghost Stories: Fuel for Modern Manga

Kaidan tales, fueled by the rich history of 18th-century storytelling, haunted Edo nights like cheap sake. Travelers huddled in inns, swapping stories of vengeful lovers and disfigured corpses. Tsukioka Yoshitoshi borrowed from Botan Dōrō – where a lantern reveals a lover’s rotting face. Modern manga artists feast on these bones:

- Tokyo Ghoul’s cannibals echo flesh-hungry yokai often depicted in the gory narratives of traditional Japanese art.

- Hellstar Remina’s planet-devouring sphere channels Hokusai’s Great Wave.

- Uzumaki’s spiral curse mirrors folklore about cursed patterns.

Japanese ghost stories never die. They just mutate – from Japanese woodblock prints to anime screens.

7. Edo Period Horror: Suffering in Ink

Edo artists weaponized realism. No fangs or claws – just a woman drowning her child in a moonlit river (Yoshitoshi’s Drowning Woman, 1890). Or a severed head gasping its last breath (Kuniyoshi’s Rokurokubi). Why such brutality? Buddhism taught that suffering clung to the living like wet silk. These prints were moral warnings sold as cheap entertainment. Mess up, and this awaits:

- Adulterers torn apart by demons.

- Greedy merchants eaten by yokai.

- Samurai dishonored by vengeful ghosts.

The horror genre wasn’t fun – it was a supernatural ethics lesson.

8. Kabuki’s Bloodstained Influence

Kabuki theatre birthed Japanese horror’s dramatic flair. Actors froze in mie poses – eyes bulging, muscles locked in agony. Kuniyoshi snatched these poses for prints. See Oiwa’s spine-contorting scream? Pure stagecraft. Even the kumadori makeup code bled into yokai designs:

- Red = heroic passion

- Blue = villainous coldness

- Green = supernatural evil

Modern anime? Demon Slayer’s demons strut with kabuki’s exaggerated menace. Even Sadako’s jerky crawl in horror movies like The Ring evokes elements of traditional Japanese art by mimicking kabuki’s eerie roppo exit runs.

9. Suehiro Maruo’s Psychological Torment

Suehiro Maruo doesn’t scare you – he violates you. In The Laughing Vampire, a schoolgirl slaughters men with a razor-blade smile. His artwork oozes grotesque detail – think melting faces and occult symbols inked like prison tattoos. But beneath the gore? Fury at Japan’s cultural amnesia. His monsters wear business suits and devour traditional geisha. Buildings crumbling into tentacles? That’s westernization as body horror. He pioneered eroguro – erotic grotesque – proving the unique blend of horror in Japanese art and horror manga could be social critique.

Modern Manga and the Evolution of the Japanese Horror Genre

10. Junji Ito: Horror Manga’s Undisputed King

Junji Ito spirals daily life into cosmic dread. A girl’s curl snakes through town, driving citizens mad (Uzumaki). Fashion models unzip their faces to reveal void (Fashion Model). He cobbles together Edo’s realism with Lovecraftian body horror. Fun fact? He collects Yoshitoshi prints. See The Lonely House – where a skinless monster peels a woman alive? That’s Ito’s source material. His genius? Making the familiar terrifying:

- Balloons with human faces (Hanging Balloons)

- Spirals in seashells and fingerprints (Uzumaki)

- Human-shaped holes (The Enigma of Amigara Fault)

He pioneered modern psychological horror – one twitching panel at a time.

11. J-Horror: Old Ghosts, New Tech

J-Horror films haunt differently because they recycle a traditional ghost through tech. Sadako’s static-filled video curse? A digital yūrei. The Grudge house? Its creaks mirror kabuki’s tsuke drum beats. Directors marinate new tech in old fears:

- Ring (1998) used a wig, Vaseline, and jerky movements – zero CGI.

- Ju-On’s stair-crawl copies ukiyo-e compositions of crawling spirits.

- Dark Water’s elevator drips with Buddhist themes of unresolved grief.

Even the vengeful ghost’s lurch comes from kabuki’s suriashi gliding walk.

12. Westernization: Japan Horror Art’s Double-Edged Sword

When Japan opened during the Meiji era, artists like Katsushika Hokusai influenced many aspects of Asian art, while others spliced Western anatomy with yokai. Yoshitoshi draped ghosts in Victorian gowns. Kuniyoshi drew samurai with Michelangelo-esque muscles. Modern horror manga? Junji Ito warps American zombies into spiral-obsessed townsfolk. Suehiro Maruo disfigures salarymen into tentacle beasts. Western horror films infect, but never conquer. Why? Japanese horror’s core remains:

- Shinto belief in spirit-filled worlds.

- Buddhist karma punishing moral failures is a common trope in Japanese horror art.

- Folklore monsters as societal mirrors.

The vengeful ghost? Still uniquely Japanese – whether she crawls from a well or an iPhone screen.

More Japanese Horror Art Gallery

Conclusion

Japanese horror art isn’t about cheap thrills – it festers. From Yoshitoshi’s grief-stricken ghosts to Ito’s spiral nightmares, it holds up a cracked mirror to Japan’s soul. These images cling because they’re folk art, religion, and social protest rolled into one. They ask: What haunts a culture? For Japan, it’s betrayal, loss, and the monsters we become.

Do this tonight: Google Kuniyoshi’s One Hundred Ghost Stories. Zoom into Oiwa’s eye or a yokai’s grin. What detail hooks your fear? That’s Edo period terror – alive after 200 years. Then watch Ju-On. See the kabuki in the ghost’s walk? You’ve just met Japanese horror art’s bloody heartbeat.

FAQs

Q: What is the significance of horror in Japanese art?

A: Horror has been an integral part of Japanese art for centuries, often reflecting societal fears and cultural beliefs. Through various mediums, artists convey the complexities of human emotions and the supernatural, making horror a compelling theme in Japanese storytelling.

Q: How did ukiyo-e artists contribute to the horror genre?

A: Ukiyo-e artists, especially during the Edo period, played a crucial role in depicting horror themes through their woodblock prints. They illustrated ghost stories and eerie folklore, capturing the imagination of viewers and establishing a visual language that resonates with the horror genre.

Q: Who are some popular Japanese horror artists?

A: Some popular Japanese horror artists include Yoshitoshi Tsukioka, whose works often featured ghostly figures and dark narratives. His unique approach to horror has influenced many contemporary artists and continues to inspire those exploring the intersection of art and fear.

Q: What is the approach to horror in modern Japanese art?

A: Modern Japanese artists often blend traditional horror elements with contemporary themes, creating a unique fusion that appeals to both local and international audiences. This approach allows for a fresh interpretation of ghostly narratives while maintaining a connection to historic traditions.

Q: How does East Asian culture influence Japanese horror art?

A: East Asian culture has a profound impact on Japanese horror art, as themes of the supernatural and the afterlife permeate the region’s folklore. This cultural backdrop enriches the storytelling aspect, allowing artists to draw from a shared heritage of ghost stories and mythological creatures.

Discussion about this post